Michigan State University is fortunate to have passionate educators who are committed to enhancing the experience of their students and who help to provide the best education possible.

The Graduate School is featuring some of these educators – graduate and postdoc educators – every month to share their unique stories and perspectives on what it means to be a dedicated educator, how they’ve overcome educational challenges, and the ways they have grown through their experiences.

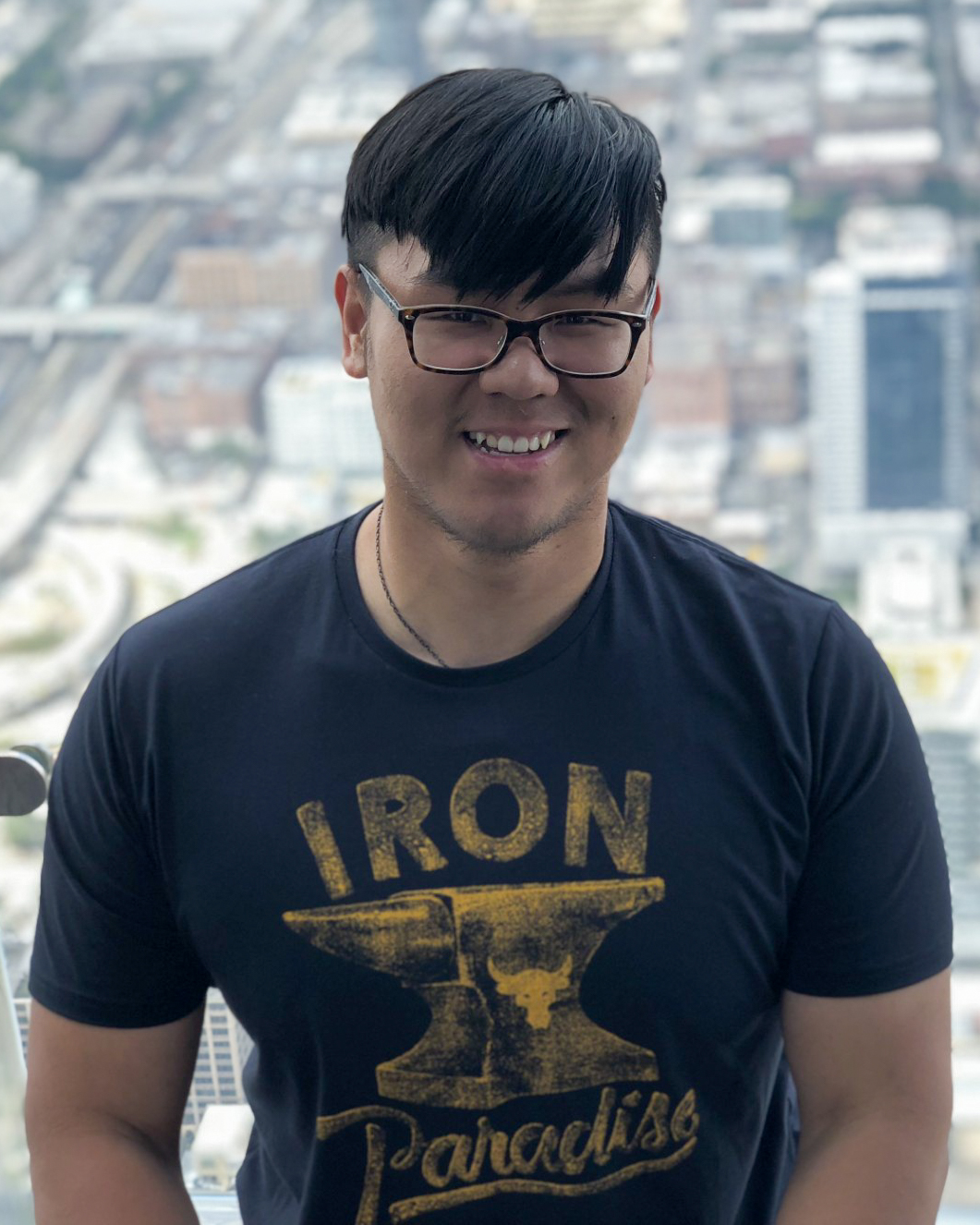

For March 2025, we are featuring Bobicheng (Beau) Zhang, a doctoral student in Cognition and Cognitive Neuroscience. In his writeup, Beau shares how he learned to refrain from making assumptions about students to foster an inclusive learning environment, as well as the importance of maintaining a good routine to prevent burnout.

What does it mean to be an educator at a university?

Being a university educator extends beyond just conveying information. It means fostering a supportive environment where students feel comfortable seeking help. Sometimes, it could also mean extra availability and individualized assistance outside the classroom.

Adaptability and receptivity are vital, particularly in understanding what helps different students grow. At a large institution like MSU, students come from such diverse backgrounds that their experiences prior to college can differ vastly, meaning that they may excel and struggle in distinct aspects of higher learning.

My first teaching assignment was amidst the pandemic, and students reacted differently to online asynchronous lectures. Some preferred the flexibility of such a format while others struggled with the lack of engagement. As educators, we should always remember that obstacles come in all shapes and sizes and try to help in as many ways as possible.

Of course, this is not limited to the teaching assistantship we are assigned to; it applies in any setting allowed by our expertise. One of the main determinants of my pursuing a Ph.D. is the amazing graduate students in my lab with whom I was fortunate to have worked as an undergraduate student.

The guidance they offered along the way was indispensable. Even though their schedules were often filled to the brim, they still helped me with programming experiments, running analyses and preparing manuscripts. They encouraged me to ask questions and make comments during lab meetings. Therefore, I aim to help undergraduate research assistants in my lab in the same manner they helped me.

A unique aspect of being an educator at a university is forging the high-level understanding of a given subject field by conveying low-level knowledge. For example, we talk about neurons in an introductory psychology course not because we want students to memorize their every function, but because they are the building blocks of the nervous system.

During my undergraduate years, I often heard professors say that it was useless to memorize all the information taught in class, and that it would be more worthwhile to try to understand the larger picture. I remember thinking I understood what they meant just because I memorized everything.

Clearly, I was wrong. Memory can fade and can even misguide us. A foundational understanding of the overarching framework and questions, on the other hand, is adaptive for any subject and can allow us to quickly piece together the low-level information we need.

Lastly, I think it’s significant to consider the role of a college education for most people. It’s likely the transition between education and what most would refer to as “the real world.” This means that, majors aside, students should walk away with the ability to critically inspect information.

A key part of graduate training is this exact skill, so graduate students are in prime positions to showcase its importance. In the information age, a considerable proportion of the information we receive daily either originates from questionable sources or includes strong personal biases. A healthy skepticism goes a long way. Only when we are confident that the information is reliable can we make informed decisions.

Challenges you have experienced and how have you grown from these?

As I started teaching, my first and foremost challenge was to refrain from making assumptions about students. Here, by assumptions, I don’t mean preconceived notions that lead to discriminatory behavior. Instead, I refer to heuristics, or automatic thoughts, stemming from my own college experiences.

A typical example could be assuming that someone is not working hard in a course when they are seen falling asleep during a lecture. It is incredibly easy to take the mental shortcut and conclude that they are lazy and/or do not take lectures seriously. While there may be a correlation between falling asleep during lectures and performance in that course, inadvertently making this assumption would preclude me as an educator, to a certain extent, from seeing the student’s full potential.

It was challenging to detect that I was making these assumptions, as it can be habitual for anyone, including some neurodivergent individuals, to leap between associations without realizing it. We all have experiences that may contribute to snap judgments or assumptions.

Nevertheless, we must understand that removing assumptions is essential for fostering an inclusive learning environment. I don’t know if many of us can truly refrain from making any assumptions, but I have learned to periodically “reset” my impression of students and remind myself that I don’t know what happens in students’ lives outside of the classroom. The only valid assumption to make is that students are here to learn and improve themselves.

Further, establishing proper boundaries, and relatedly, time management, were also challenging. The difficulty resides in maintaining the delicate balance between the desire to help and preserving time for my other responsibilities. As an educator, I strive to be as available as possible for students. However, in my early years, this meant spending too much time answering emails or preparing class materials, which would bleed into my other responsibilities.

To set a healthy work-life balance, I learned to dedicate certain times of the day every day to teaching-related work. More importantly, I would constantly remind myself that, like research, teaching is also a marathon, not a sprint. There is little use in rushing to complete it.

What value do you see in teaching professional development?

General pedagogy training, like the workshops offered by the Graduate School, can be very helpful for those who are just starting to teach. They provide systematic help to those who may not be familiar with a college teaching environment. I have certainly learned about tips and tricks that I was unaware I needed.

They are also great opportunities to form connections with other like-minded educators. It is sometimes easy to forget that education is a collaborative effort, so being able to communicate with peers from different units is invaluable. These communications would also force us to reflect on our past teaching practices and allow us to address the problems that we may miss on our own.

As we move on and gain more teaching experience, the value of professional development can vary. Graduate educators have vastly different strengths as a result of our respective discipline and individual experiences, so we may benefit more from workshops focusing on areas that are not typically highlighted.

For example, the workshops focusing on teaching statements or diversity statements have been very helpful as some of us had struggled formulating core values and beliefs that are reflected in our day-to-day operations. These could also be sessions that simply promote communication among graduate educators across different units.

What is one piece of advice you would give other graduate educators?

Perhaps the worst phenomenon for graduate students is burnout. It is our passion for research and/or teaching that keeps us going. When that passion fades, it can be incredibly difficult to stay motivated.

If I had to give one piece of advice, as someone who has dealt with burnout, it would be to adopt a good routine and maintain optimal physical and mental health during downtime when there are fewer deadlines; so that when the pace accelerates (or when things go wrong, which they likely will in academia), you have the capacity to handle it effectively without letting it impact your other work.

If I may borrow from introductory psychology again: Research shows that acute stress response is beneficial as it mobilizes resources where appropriate to boost cognitive abilities, whereas chronic stress response is detrimental because spending too much time in an alarmed state places an unnecessary burden on our body.

If we can maintain a good routine with a good work-life balance as our baseline, when challenges arise, whether it’s qualifying exam or grading assignments, we will be able to face them without exacting too much stress and feeling burned out. So, plan ahead and allow yourself time to destress, even if it is just a few hours every week.

What do you enjoy in your free time?

I enjoy going to the gym or playing video games when I want to relax after a long day. Exercise in particular is very exhilarating for me. Sometimes, I also like to tinker with mechanical keyboards. Because so much of my day is spent typing, I like to make sure that the tools I am using are pleasant. For the same reasons, I also collect fountain pens as I find them more satisfying as a writing tool.